I was fortunate enough to be able to study abroad in Spain a few years ago. It was a great time in general, but I especially enjoyed going to museums and seeing the variety of weird medieval stuff they had on display. The description placards rarely satisfied me–though I might learn plenty about what materials were used to build something or when the creator was born, I would be left squinting at depictions of brightly colored monsters on somebody’s dresser or what have you for ten minutes at a time, wondering, what the f— is that?

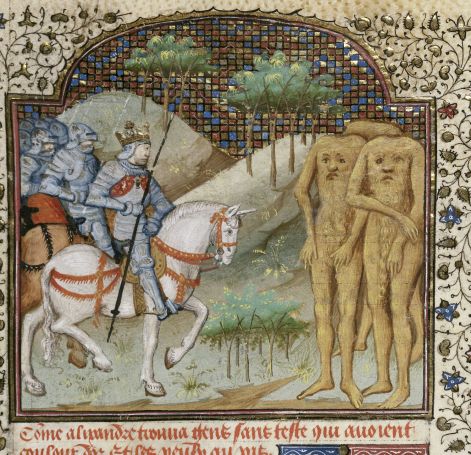

Imagine my delight on recently happening upon an image like this, then:

“…oh hey…”

…next to an actual explanation!

The Blemmyae–or Blemmyes, or akephaloi–are pretty old mythical beings–older than Christianity. They first show up as far back as Herodotus’s Histories (440 B.C.): unnamed headless humanoids spoken of in the same breath as horned asses and men with dog heads who lived together on the “exceedingly mountainous and wooded” Eastern edge of Libya, on the outskirts of the “civilized” world. From there on out, the Blemmyae would be confined to outskirts, even as the world expanded and the definition of outskirts changed.

Mela (the earliest Roman geographer, first century A.D.) was indirectly responsible for giving them their name. He wrote that there was a tribe near Nubia with the name “Blemyae,” and then Pliny the Elder (the guy who wrote the first encyclopedia) turned around and said that that tribe was the one that might be described as “[having] no heads, their mouths and eyes being seated in their breasts.” His is the description that has defined the Blemmyae since, and led to many an amusing illustration.

“My belly hair starts at my lip!”

Mind you, there was an actual nomadic kingdom of people in that area called the Blemmye that existed in Nubia from around 600 B.C. to 300 A.D.. They were a subset of the Beja people (who are still around today), and had entirely ordinary heads. Modern commentators guess that the rumors of their “headlessness” might have come from unusual hairstyles, shields with faces on them, or an ability to raise their shoulders high and lower their head as they marched forward into battle. That, or Pliny was just xenophobic and making stuff up.

Pretty easy to see through, right? You would think that people would have figured that out and let the idea die, especially as knowledge expanded and it became apparent that most everyone’s neighbors were just regular people. There was also critical physiological questions that hadn’t been answered: if the Blemmyae’s faces were in their chests, where were their brains? Their other organs? It was all a little suspect, but the idea of people with faces in their chests turned out to be stickier than simple explanations or common sense.

The Blemmyae appeared in writings in the 7th or 8th century, and then again in 1121, where descriptions now have them at 12 feet tall and 7 feet wide, and of a golden color for some reason. These were incorporated into the Alexander Romances, where they were shrunk back down again to 6 feet tall and then 30 of them captured to be shown to the world.

Then they spread. Medieval maps showed them further east into India and the the area north of the Himalayan mountains. They appeared in The Travels of Sir John Mandeville described as “folk of foul stature and of cursed kind that have no heads. And their eyes be in their shoulders” on an island in Asia. Sir Walter Raleigh, an English explorer, claimed that they were also in South America: “eyes in their shoulders, and their mouths in the middle of their breasts, and that a long train of hair groweth backward between their shoulders.”

So they were everywhere–just nowhere where Europeans could easily go and see them with their own eyes. And at first they were just a morbid curiosity, something to be frightened by only because it’s different looking.

Then came Shakespeare.

Othello, Act 1, Scene 3: “It was my hint to speak—such was my process—And of the Cannibals that each other eat, the Anthropophagi, and men whose heads Do grow beneath their shoulders.”

Here is why we learn to be careful with sentence structure, ladies and gents. Ole’ Billy meant that the Anthropophagi were the cannibals, and that then there was a separate group (the Blemmyae) with heads beneath their shoulders. Instead, people heard that and went, “oh wow. Monsters with faces in their chest that eat people! Gee willikers!”

Which is how Blemmyae images morphed from this into this.

These days, the Blemmyae themselves don’t seem to be in style so much as the Anthropophagi-Blemmyae combination does. Rick Yancey’s Monstrumologist series seems to have something to do with it that…researching this post has made me put his books on my reading list. Still, though blood-soaked cannibals are great fun, there will always be a soft spot in my heart for anything that looks like this:

“Ladies.”

Just can’t say no to that kind of charm.

Has excessive slouching led people to believe you might be one of the Blemmyae? Do you think it would be harder or easier to brush your teeth if your mouth was in your chest? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

ALL IMAGES: Courtesy of Wikimedia commons, and people long dead. Featured image by Hannah Wernecke.

0 Comments