It’s a new decade, everybody! This is the time when everyone looks at how much has happened over the past few years and makes guesses about what will happen next. We live in an era of constant and dramatic change; as interesting as that can be, being stuck in such flux is not always pleasant. As my gift to you, let’s explore something that has not changed: old guilts and fears from way back in the beginning of human civilization.

Bad deaths all around

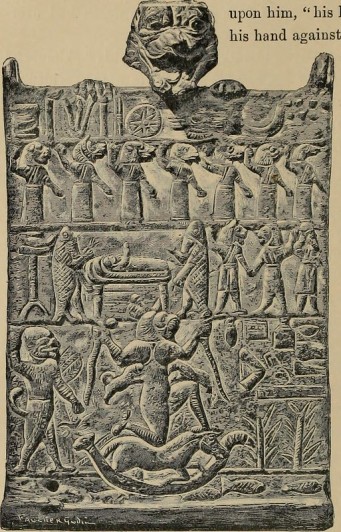

The Edimmu (or Ekimmu, but Wikipedia, Unimpeachable Source of All Knowledge, says Edimmu is the right way to go so we’re going with that) is often referred to as the oldest vampire legend in history. It was born in our first civilization–in Sumer, cerca 4000 B.C.

Between inventing the 60-minute hour and beer, ancient Sumerians worried a lot about what happened to the spirits of people whose lives ended in a less-than-ideal manner. After all, there are many ways to die poorly: if someone murders you, if you get in a freak accident, if you get lost in the desert, if you bleed out during childbirth, if you perish without ever having known love, etc. Or maybe you die in a normal way, but nobody bothers to bury you and your corpse is left out to rot. What happens then?

When fate deals out such terrible things, it is like justice has been snatched away. Indeed, that is what “Edimmu” translates to–“that which is snatched away.” And you’d better believe that someone will pay.

Of course, that someone might not be the person who wronged the angry soul–the Edimmu–in the first place. Edimmu don’t really discriminate that way. But hey! At least they’re making someone as miserable as they are.

Nagging guilt

Being more spirit-based than your traditional vampire, the Edimmu doesn’t have a real *look* in the way that a Nosferatu (or Edward Cullen) does. Some depictions cast then as winged demons, walking corpses, or shifting shadows, but more often they have no corporeal form at all. Instead, your only warning of their presence is a cold draft that raises the hair on the back of your arms. This makes the Edimmu damn hard to run away or hide from–you can’t avoid what you can’t see.

Compounding the problem is how easy it is to catch an Edimmu’s interest. You might infer from the aforementioned extensive list of bad ways to die that there would be Edimmu being created constantly. You would be correct. The odds are in no one’s favor. Even if you went about your life never killing or wronging anyone and making sure that everyone you knew was buried quite well, one day you might happen upon a corpse or ingest a little ox meat and boom! You’d be cursed with the company of an Edimmu.

Once an Ediummu is latched onto you, you’re in for a ride. Lower-key tales of Edimmu cast them as mere irritants who, banshee-like, will sit outside your house and wail when someone is about to die. Moderate-key versions describe them blowing through your house, stealing away the life force of those they pass through (especially if the victim is a child). Then there are the more intense versions of the myth, in which the Edimmu telekinetically attacks you on and off over the course of years, slowly crushing away your will to live as they give you hope that they’ve finally gone away before coming back again. Once they’ve sucked the last of your life out of you, they possess your body, and then go about doing the same thing to those you love.

So really the moment you realize that you’ve got an Edimmu on your tail, it’s best to nip that garbage in the bud.

How do you stake a ghost?

One of the reasons that we know about the Edimmu at all was that we found a spell a mother wrote in hopes of keeping the monster away from her children. When things like that failed, exorcisms were the way to go. These involved not only invoking one of the three most powerful gods of Sumerian lore, but also setting a bunch of stuff on fire. (This, as one author points out, might be the birth of our conception of how to handle modern vampires, i.e. burning them or subjecting them to the biggest fireball of all: the sun.)

Though such tactics might have been effective in individual cases, the legend of the Edimmu continued. After Sumer faded into the history, the vampire-ghost fever was picked up by the Babylonians, then the Assyrians, and then the Egyptians and beyond. It did it not even stay isolated in the Middle East–the Inuit have their own variation of the Edimmu, way over on the other side of the globe. Today, it is said (by internet sources citing nothing, but still) that the Edimmu lives on, plaguing those experiencing homelessness with disease and despair. Certainly their legend has influenced countless other ghost and vampire myths that we now take for granted.

Whether it’s our love of beer or our fear of pissing off those who have passed away, it’s nice to know that at least in some respects, humanity has never changed.

What burial rite might you be most likely to screw up and get an Edimmu on your case? Share yours in the comments below.

IMAGE CRED: Internet Book Archive on Flickr for the relief, and Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) on Wikimedia Commons for the intense worshiper. Egor Myznik for the featured image.

0 Comments