Content warning: suicidality.

In the late 2000’s, a 40-year old school teacher came to visit Dr. Francesca Anzellotti at the Department of Neuroscience and Imaging at G. d’Annunzio University in Chieti, Italy. The teacher had been referred there after suffering with epilepsy and depression for years. Previous doctors had tried several medications to help, but none stuck. Now things had come to a head: desperate, the teacher had tried to poison herself twice in the last 12 months.

To Anzellotti, the teacher seemed ill at ease–unusually so, even for a patient with her history. Something was off. The teacher talked incessantly, but refused to discuss what was bothering her. Anzellotti performed some cognitive tests, which came back normal. She turned to a psychological assessment. In the teacher’s agitated chatter, there were hints of peculiar events. But every time the teacher got close to talking about them, she’d pivot and change the subject. Anzellotti asked her to elaborate. The teacher refused. Anzellotti pressed harder, and, at long last, the teacher gave in.

She hadn’t attempted to kill herself because life was colorless. Nor because of any physical disruption from her seizures. She had tried in a frantic effort to escape. Because every day, since she was a preteen, regardless of all the medications she’d tried, regardless of whether she was alone or with others, the teacher had been visited by an exact duplicate of herself: a pale double with her same thoughts and actions, staring back at her from across the room.

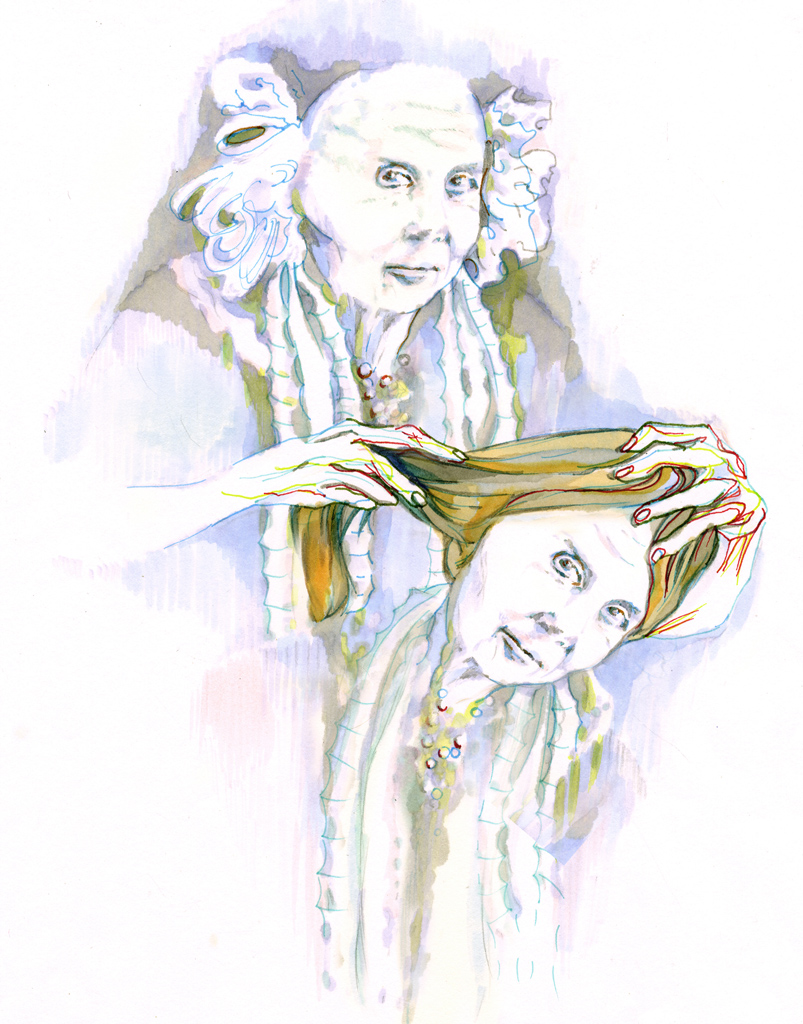

Dead ringers

If you’re in the U.S., you’ve doubtless heard the term “doppelgänger.” You’ve probably used it yourself: maybe to describe a friend who looks like Willem Dafoe, or to laugh about two people wearing the same orange sweater to a party. You’ve probably also seen the doppelgänger trope (over)played out in fiction–the intrepid hero suddenly comes face-to-face with their evil twin, and the friend/love interest has to decide which one is real and which one to shoot.

But the history of the doppelgänger is much longer and deeper than that. We got the name from German folklore; it means “double goer.” Traditionally, “doppelgänger” referred not so much to a physical twin, but to apparition of a living person (as opposed to someone who is dead). It’s worth noting that there are versions of this idea across cultures and time periods (Zoroastrianism, ancient Egyptian mythology, Greek myth, Norse mythology, and Hopi legend, to name a few). But today I want to focus on the nice and sinister German version, which has influenced how Western culture has viewed doubles for the last few hundred years.

The rules of this version are simple: Encountering a doppelgänger–even a doppelgänger of someone else–is super bad news. If you see one of a friend, it’s a sign that your friend is in terrible danger. See one of yourself, and you can expect imminent death.

Though they may look like you, and share your thoughts, the doppelgänger is not your ally. They may try to appear as one, but their “help” will be your undoing. Worse, they might actively undermine you by impersonating you, setting you at odds with friends and family. Perhaps one or two people would sense that something is off: doppelgängers don’t cast shadows or have reflections. But how many would look closely enough to tell the difference?

Repeating history

The “evil twin” doppelgänger vibe has been reinforced in literature a dozen times over. In “The Poor Clare” by Elizabeth Gaskell, a demonic double curses a young woman and keeps her from the love of her life. In Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “The Romaunt of Margaret,” a pale doppelgänger approaches a woman by the waterside to systematically unravel her spirit. Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson” has a doppelgänger picking the narrator apart when his morality fails, and Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Shadow” has one enslaving the protagonist and then killing him to avoid discovery. You’ll notice that all of these end badly, and they’re not alone: the protagonists in Dostoyevsky’s The Double, Oscar Wilde’s The Portrait of Dorian Gray, Franz Werfel’s “Spiegelmensch,” and Friedrich von Gerstäcker’s Der doppelgänger also all die or go insane shortly after coming face-to-face with their uncanny twin.

But for some people (like our Italian teacher), doppelgängers are not relegated to fiction. One researcher in 1884 reported the case of a man who could induce a hallucination of his doppelgänger at will. Problem was, that double started to show up without his say-so, and increasingly often. The man shot himself to escape. Also in the 1840’s, the students of a woman named Emilie Sagée repeatedly saw her doppelgänger when Sagée was somewhere else. The sightings left her drained and helpless. The students tried to touch the apparition, and their hands passed through–they said it felt like thick fabric.

Then there are the cases from famous people. English poet Percy Shelley met his doppelgänger on a terrace; a friend saw the same doppelgänger walking past shortly after Shelley had, confusing and frightening her. Shelley drowned in the Bay of Spezia less than a month later. Catherine the Great was aroused from bed one night by her servants, who had just seen her double in the throne room. She ordered the copy to be shot, but died shortly thereafter. And then there was Abraham Lincoln. After his inauguration, he saw a double reflection of himself when looking in the mirror: a second face next to his own, pale and sickly. His wife was worried that this dual image was a bad omen. She didn’t want to be right, but it seemed to mean that Lincoln would serve his full first term, but not live to finish the second.

Parallel phenomena

Dr. Anzellotti set up equipment to monitor the troubled teacher’s brainwaves. They were going to try to induce one of these doppelgänger experiences in the lab. She told the teacher to give her a signal the moment the doppelgänger arrived, and then sat back to wait.

And then, when nothing happened, packed up the equipment and told the teacher they’d try again.

And then again.

Visit after visit, the doppelgänger refused to appear. It seemed that they should despair of it ever cooperating. Then, one day, in the middle of a session, a sharp hand gesture from the teacher. Anzellotti checked the monitors. The semi-regular EEG lines had exploded apart from one another and into a fuzz–epileptic activity. Anzellotti turned to the teacher, but she appeared still.

The teacher would later report that she suddenly felt unreal–as if her body weren’t quite right in space. Then the doppelgänger was abruptly in front of her. It was upright, clothing identical, facial expression identical. In her panic, the teacher couldn’t tell which of them was real. Her thoughts were the doppelgänger’s thoughts, her fear its fear. It looked back into her eyes, motionless. Silent.

As the brainwaves continued to spike, Anzellotti pressed the teacher with questions. But suddenly, she stopped responding. Her eyes went fixed, and she, too, fell silent.

Later, she would have no memory of that gap.

Double-checking the data

Thanks to Anzellotti and others, there are scientific explanations for the doppelgänger phenomena–or at least, for some of it.

It’s helpful to understand that there are all kinds of ways we can see a weird vision of ourselves. From a clinical standpoint, doppelgängers are part of a broader umbrella of phenomena called autoscopy (from the Greek words “autos” (self) and “skopeo” (looking at)). Autoscopic experiences include feeling a presence at the fringe of your vision, being out of body and seeing yourself from afar, looking in a mirror and not seeing yourself at all, and–my personal favorite–“inner heautoscopy,” or seeing your organs outside of your body.

Meeting your doppelgänger (“heautoscopy”) is a cousin to each of these, but it has its own peculiarities. While other autoscopic phenomena last for only seconds or minutes, heautoscopy can last for hours. Doppelgänger appearances are also more 3D than the other ones–you can see your double from a number of angles–and can come accompanied with weird sensations and dizziness. Finally, as Anzellotti puts it, “positive and neutral emotional experiences are especially rare in he-autoscopy.”

Based on our schoolteacher’s case and others, the basic hypothesis is that autoscopic experiences are hallucinations brought on by a misfiring of electricity. When there is too much stimulation at 1) the junctions where parts of the brain communicate with each other or 2) where the brain processes sensory input, we see things. But figuring out how it all comes together is a challenge. There are a lot of different ways we orient ourselves and find a sense of identity. There are even more ways that process can go wrong.

Regardless, it seemed clear to Anzellotti that to resolve the epileptic seizures, the teacher needed a specific anticonvulsant she hadn’t tried before. The schoolteacher took the medication, and in the following two months, the doppelgänger visits disappeared. Unfortunately, the trauma didn’t. The teacher was referred out again, this time to psychiatric care, to assist her on the road to recovery.

Clone wars

So does everyone who sees a doppelgänger have some kind of epilepsy? Perhaps. Electrical misfirings could explain the accounts of people seeing doubles of themselves. But they don’t explain the accounts of people–sometimes multiple people–seeing doppelgängers of others.

As you can tell by the length of this post, I think doppelgängers are super interesting. They force a lot of existential questions. Of course visions of your double make you question who you are, and what makes you you. But why is it that doppelgänger sightings are almost universally negative? Are we really that at odds with ourselves, that when we see another version of us, we automatically interpret it as evil? When we come face-to-face with our duplicate–the person we know and can sympathize with best–why is the impulse not to team up? Do we hate ourselves, or are we simply that afraid that this world ain’t big enough for the two of us?

Maybe doppelgängers are the fault of physiology. Or maybe it’s psychology. Maybe they’re elaborate ghosts, or maybe other dimensions are overlapping with our own. Genetically humans aren’t that diverse, so it’s very possible that random chance spits out a person that looks exactly like you. Maybe it’s that. Maybe it’s nothing to be afraid of.

Regardless, you might want to watch out for that dillhole wearing the same shirt as you at work.

If you were to come across your doppelgänger right now, would you be satisfied with their hair? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

IMAGE CRED: Thanks to Galiaoffri for the exciting illustration, Photos_frompasttofuture for the double berets, Brian Lundquist for the smoking thinker, Alina Grubnyak for the other thinker, and Juan Domenech for the philosophical birds. Finally, a big thank you to Jessica Felicio for the main image.

0 Comments